Editor-in-Chief

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Automated bending keeps the pieces flowing

Emerson Network Power's Liebert business division finds technology maximizes its lean manufacturing efforts

- By Dan Davis

- March 10, 2011

- Article

- Bending and Forming

Figure 1: Emerson Network Power’s Liebert business unit installed an EBe servo-electric panel bender in 2008. It has a maximum bending length of 100.39 in. and a maximum opening height of 8 in.

A healthy skepticism about robotic bending still exists in the fabricating community. People fear having to program the robot for the hundred or so part numbers that might be suitable for the bending cell and are anxious about having to deal with the many different end effectors that may be necessary for picking up punched blanks.

That doesn't mean people aren't sold on automated bending, however. Emerson Network Power's Liebert business division in Columbus, Ohio, produces heating and cooling systems for companies that need to maintain precise temperatures for reliable IT equipment performance in their data centers. In one of its five North American plants, a stand-alone panel bender is used to bend corners automatically. A loading arm places precut blanks into the machine, and the machine bends all the corners and sends the parts on their way. Efficient and accurate—that's how the company viewed the panel bender.

As Emerson's Liebert facility in Columbus looked to move away from batch manufacturing and adopt more of a one-piece-flow approach to production in 2008, the manufacturing team wondered if automated bending could help. More specifically, could such a cell assist with larger parts, which could be as tall as 99 inches and as wide as 40 in., and work in an environment where more than 200 part numbers would be thrown its way?

Emerson found its answer, and it wasn't a robot. And it wasn't hydraulically powered. It was a servo-electric panel bender, and with a couple of tweaks, the equipment ended up being just the right engine to jump-start the facility's lean manufacturing efforts.

A Better Way of Bending

Emerson found the right machinery after watching a Finn-Power servo-electric Express Bender (EBe) do its job at another metal fabricating facility. The company liked that NC servo axes—not hydraulic cylinders—controlled the bending blade movements, in both the vertical and horizontal direction, and the upper tool movements. They believed the servo-electric technology would contribute to much more precise control of the bending process and would require less maintenance because the shop floor wouldn't have to worry about hydraulic fluid.

Emerson also was familiar with Finn-Power equipment, having made its first purchase in 1997. The Columbus location had four of the Shear Genius punching/shearing machines and one Laser Punch combo, while its two other Ohio locations had seven more punching/shearing machines and its two Mexico locations had 11.

That excitement about the servo-electric technology and familiarity with the equipment manufacturer led to a $1 million investment in an automated cell with a new Shear Genius, an EBe automated bender (see Figure 1), and a picking/stacking robot to move blanks from one station to the other. The cell was installed in May 2008, and the crew was running production volumes only three months later.

The potential that the manufacturing team saw in the equipment was evident early on as they worked to ramp up production. Jack Somerville, Emerson's manufacturing engineering manager, said the bender's automatic tool changer allowed the shop floor to run any part, any time, with very quick changeover—about 20 to 30 seconds.

"The Finn-Power equipment gives us the opportunity to run multiple part numbers at once. We're out of that batch mentality now," Somerville said.

The EBe doesn't handle all of the company's 4,000 sheet metal part numbers, but it does process 250 different part numbers, 50 of which are high volumes. Fred Crumb, Emerson's production line manager, estimated that 20 percent of the volume in the sheet metal department runs through the EBe.

Figure 2: Parts can exit the automated bending cell in two ways: to the side onto a conveyor that feeds the welding department or straight ahead for direct unloading.

"The EBe is a hungry monster. It can devour parts about twice as fast as punches can make them, especially for ours because we do a lot of large panels," Somerville said. "So we can actually load a second part number or even two other part numbers on the picking/stacking robot that come from other Shear Geniuses. We can run multiple part numbers at one time."

Even with three of the punching/shearing machines regularly feeding the bender, it keeps the pieces flowing through the cell. The quick tooling changeouts are a big reason. Even when manual tooling changeouts are needed—only about 10 to 20 percent of the time—the one operator running the bending cell can make the change in three minutes. That compares favorably with the 18-minute tooling changeover required for one of Emerson's seven traditional press brakes at the Columbus facility.

"There is a savings of 30 percent in labor when running the EBe over the manual brake," Crumb said.

Emerson now is seeing the bending cell produce a panel every 40 to 50 seconds. That includes even the largest of its panels that used to require two operators working around a press brake. The cell produces about 300 parts per shift, running three shifts during the week.

As of the end of last year, Somerville said the EBe had contributed savings totaling more than $750,000—mostly related to a reduction in labor costs and decreased setup times.

The Real Fit May Be the Flow

Cost savings are always an important consideration in any equipment investment plan, but the real story may be how the new bending cell affects the shop floor. If Emerson employees experienced difficulty in visualizing one-piece flow, the new equipment made the concept crystal-clear. A few tweaks to the standard bending cell design helped to accomplish that.

During the final testing of the bending cell in Italy before it was sent to the U.S., Emerson requested that Finn-Power alter the way the equipment unloaded parts. The lean manufacturing disciples within the company knew that loading bent parts onto skids and then moving them in a batch to the welding area was not going to support the one-piece-flow concept.

So Finn-Power modified the logic in the PLC and reconfigured the unloader rails, creating two exit points (see Figure 2). Parts can exist out of the bender and down a conveyor to the welder, or they can exit at a 90-degree angle for unloading onto skids.

Parts destined for welding travel about 10 feet on the conveyor to where an operator gas tungsten arc welds the corners. The parts then continue down the conveyor to the resistance spot welding station where another operator puts stiffeners into the panels. The custom-designed spot welder has six welding heads, each one attached to its own servomotor; as different panels come through, the servos can alter the position of each welding head while the PLC automatically calls up the weld sequence, allowing for different combinations of panels to be sent through one after the other. It takes only about five seconds for the changeover, according to Somerville.

When welding is complete on the panel, welders place the part on a skid for delivery to the kanban area where the assemblers pick the parts needed to complete the heating and cooling products. The entire process—delivery of raw stock, punching, bending, and welding—is now done in about six minutes compared to the two hours it took before the bending cell was installed.

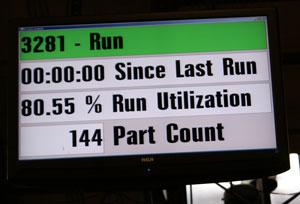

Figure 3: The automated bending cell is connected to a machine monitoring system that displays the run-time, downtime, and piece count for the cell on a 40-in. LCD monitor hung overhead.

The amount of time to complete larger orders and replenish inventory as part of the kanban program also has decreased significantly.

"The EBe has basically lowered our inventory and our time of supply from about five to seven days to about one to three days. It's had a huge impact," Somerville said.

The welders are pleased with the new work flow. They are getting parts with exact bends. Somerville said the new bender has a capability of ±0.010 in., which is a big improvement over the manual press brakes, especially on large panels. And these precise bends are not only good for parts with square corners, but also specialty panels. About half of Emerson's panels have a "chiseled" look with 45-degree angles at the corners. The manual press brakes struggled to deliver consistent results on these types of panels, but the new bender doesn't, eliminating the adjustment time welders needed to ensure the corners fit up correctly.

Actually, at Emerson the welder also runs the EBe. If the bender isn't producing the exact bends necessary for quality welds, the welder can stop the bending cell and make the adjustments necessary to get the needed results. The only other person working in the cell is the operator loading steel onto the Shear Genius and supervising the punching activities.

The conveyor to the welding department wasn't the only change that Emerson asked for. It also requested that Finn-Power technicians work to connect Emerson's machine monitoring system to the new automated cell. It took some tedious development time, but the parties ultimately developed the right output signals between the PLC and Emerson's own computers.

With that connection complete, the overhead monitors were activated (see Figure 3). The shop floor now has a real-time look at how the automated cell is operating: whether it's running, it's blocked, or it's waiting for a part. The immediate feedback energizes the shop floor and has everyone working to increase run-time in the cell.

When asked to reflect on the biggest change since the bending cell was installed, Somerville doesn't really focus on the equipment. If anything, the newfangled technology forced everyone to rethink old-school habits. They actually had to talk to each other.

"The biggest cultural change was getting operators to talk to each other. In our shop, we had five SGs and eight brakes. It was a job shop mentality," Somerville said. "When the Shear Genius operator was done, he stacked his parts, put them on a skid, and brought them over to the brake operator. Now it was his job to do."

That's not the case now. The operator at the punching machine regularly has to communicate with the welder/EBe operator at the end of the line. Are any manual tool changes going to be needed on the bender? What parts are going to be run today? In what order are they going to be run? Is an extra skid needed for the picking/stacking robot? Will the welder be able to handle a combination of parts heading his way?

"There were some communication and cultural changes that took them a while to work through; however, now they work well together as a team," Somerville said.

Figure 4: With the use of custom-made carts, Emerson has decreased the use of lift trucks. This has decreased downtime, because people no longer have to wait for lift trucks to deliver parts, and simultaneously created a safer environment by reducing the potential of a lift truck getting into an accident.

Moving in the Right Direction

Emerson is still pushing change, even with the bending cell making such a big impact. It currently is focusing on some of the less technology-intensive aspects of manufacturing.

For example, the shop floor is trying to adopt more of a kitting approach to manufacturing. All the parts for a particular assembly might be nested on one blank using Finn-Power software, and after the parts are punched, they are moved to a press brake where the different-sized parts are bent with the fewest number of tooling changeovers possible. Upon completion, they are sent as a kit to the assembly area. Somerville said on-time delivery of goods has dramatically improved in the short time Emerson has been producing parts this way.

In another example, Emerson is applying lean principles by trying to depend less on skids and lift trucks and rely more on custom-made carts with plastic tops that expand to accommodate very long parts (see Figure 4). When a punch job is complete, parts are placed on a cart and moved to a staging area until the press brake operator pulls the cart in for his next job. As a result, the two lift truck drivers on the day shift have reduced their number of moves from 800 to 300 per shift. Now the flow is leaner and more visual, with fewer delays waiting on lift trucks.

"The challenge is to get leaner and more cost-effective," Somerville said. "It's about how you combine the right kind of technology with a very simple way. We have the Finn-Power Shear Geniuses and the EBe, which are very complicated machines, yet we came up with these simple carts that have allowed us to lower our costs. It's always about combining those simple lean principles with the right technology."

Emerson Network Power, 1050 Dearborn Drive, Columbus, OH 43085, 614-888-0246, www.liebert.com

About the Author

Dan Davis

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8281

Dan Davis is editor-in-chief of The Fabricator, the industry's most widely circulated metal fabricating magazine, and its sister publications, The Tube & Pipe Journal and The Welder. He has been with the publications since April 2002.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI