Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A new business model, a new structure—a new business

Indiana fabricator looks inward to grow

- By Tim Heston

- March 26, 2014

- Article

- Shop Management

John Axelberg grew tired of the griping. Year after year the president and CEO of General Sheet Metal Works (GSMW) attended meetings with other manufacturing leaders, and most ended the same way.

“Every time I got together with a group of business leaders, I noticed that the discussion devolved into a gripe session about the quality of the available workforce,” he said. “People have been griping for decades.”

Nine years ago he attended a business roundtable organized by Goshen College, not far from the fabricator’s home in South Bend, Ind. There he met Taylor Lewis, a business consultant who specialized in organizational development. Today, as GSMW’s chief operating officer, Lewis helps manage a vastly different organization, one where few complain about the lack of available talent.

The griping about skilled labor, Lewis found, was a symptom of a larger problem. The company had plenty of engaged individuals who, if given the opportunity, could gain more knowledge and become even more productive. After all, GSMW continued to grow, year after year, at a compounded annual growth rate of nearly 10 percent since 2005. Some growth rates from year to year, particularly after the recession, were more than 20 percent. Employees, Axelberg said, made that happen (see Figure 1).

Because of that growth, Axelberg decided it was time to look deeper into his company, and the steps his executives took over the past two years tell a story of introspection, debate, and detailed analysis into how the fabricator does what it does, and why. Amid all this, they asked a deceptively simple question: What kind of business are we?

Uncovering the True Problems

It’s an odd question for a 92-year-old enterprise. In 1922 Axelberg’s grandfather, H.P. Axelberg, launched GSMW as a sheet metal shop specializing in architecture and ventilation. During its early days the shop built paint booths, dust collectors, and air handling systems for the nearby Studebaker assembly plant. It also made metal roofing and ventilation systems for the University of Notre Dame (see Figure 2).

By the 1950s, a separate division was launched—a five-person team that focused on metal component manufacturing, supplying parts to companies like Wheel Horse, one of the pioneers of tractor lawnmowers. What began as a five-person team evolved over the decades to become the 200-plus employee company it is today, with a location in South Bend and another in Tomah, Wis.

The company survived the Great Depression, the collapse of Studebaker, and the most recent Great Recession. “In spite of the obvious problems related to growth, to survive all this through the years required an extraordinary commitment from employees,” Lewis said. “After the 2008 downturn, they found the company was growing so rapidly that they could barely keep up with the growth. And they were doing it with a very thin management structure.”

Lewis was convinced that the problem wasn’t about GSMW’s people, but instead related to the growth itself. The business was growing rapidly not because of new sales activity from new customers, but rather because existing customers were happy with GSMW’s quality, service, and pricing, and hence were giving the fabricator a greater percentage of their business—all good things.

But from a process perspective, a lot of things weren’t connected or integrated. As more and more orders flowed into the system, the complexity increased and details got missed. Whose job is it to get this done, and how did it fall through the cracks? Too often nobody could answer these questions.

Figure 1

John Axelberg, president of General Sheet Metal Works, whose grandfather founded GSMW in 1922, initiated an effort to restructure the company two years ago.

This resembles the growing pains of a lot of fabricators, as evident by the writings of various consultants in the metal fabrication arena, including Gary Conner of Sparks, Nev.-based Lean Enterprise Training. In the early chapters of his book, Lean Manufacturing for the Small Shop, Conner describes how so many job shops launch as small, in-the-garage enterprises. It’s a fast-paced, get-the-job-done atmosphere. But as the shop grows, the informal atmosphere remains. New employees develop their own processes, often using their own terminology and naming conventions. Nothing is formalized, and everything is fluid.

The lack of bureaucracy is looked upon as a good thing, separating the company from larger, lumbering corporations that can’t move as quickly to satisfy changing customer demands. But at some point, the lack of formalized processes causes problems, and this is essentially what happened at GSMW over decades of continual growth.

Through the 2000s the company grew extremely rapidly. Revenues by 2003 were $16 million; by 2008 they were $30 million; and by 2013 they reached $50 million. The extraordinarily rapid growth, though encouraging, didn’t come without some major growing pains.

No one wanted to create a burdensome bureaucracy, but as GSMW’s executives found, bureaucracies are characterized by processes, and carefully designed processes and controls need not be burdensome. In fact, what makes them burdensome isn’t the formalized job descriptions and procedures themselves. It’s the fact that those descriptions and procedures don’t support what really drives the business. To find that out, the people at GSMW had to discover what kind of business they had.

Discovering a Business Model

When Lewis met Axelberg at the Goshen College roundtable, she had a master’s degree in management science/business administration (MMS/MBA) and was working on her doctoral degree in clinical psychology before shifting gears and completing her doctorate in business and organizational psychology to further her business consulting practice.

As part of the Goshen College program, she was facilitating a group of second- and third-generation business owners in understanding how family dynamics play out at work. After the group disbanded about three years ago, she continued to work with Axelberg periodically until about two years ago, when she started consulting with GSMW on a long-term assignment focused on helping him develop his executive leadership team. Last year she was brought on permanently as vice president and chief operating officer (see Figure 3).

As part of the initial consulting project, Lewis posed some core questions to leadership: What kind of business is GSMW? What is its economic model? What defines its core process? At first, the answers skimmed the surface. It’s a contract manufacturer, obviously. But as the executive team found, that description didn’t help much and, in fact, led to some deep-seated misconceptions. Employees saw the fabricator as a maker of parts and subassemblies. But as everyone soon discovered, customers perceived their company very differently.

As Lewis explained, businesses follow various business models, but most models fall into one of three general categories. One centers on product innovation. Companies like Apple and Panasonic fit this model well. Of course, like many metal fabricators, GSMW doesn’t produce its own products.

Another business model, categorized under the technical name of infrastructure management, focuses on production. These maintain the “infrastructure” for producing large quantities of a consistently demanded product. They squeeze out as much cost as possible from the production process. This model often has what Lewis called a “machine bureaucracy,” which entails massive capital expenses, a relatively centralized structure for decision-making, highly formalized rules and regulations, and relatively low employee expenses.

It promotes producing as much as you can with as few employees as possible. Information technology and its server farms fall neatly in this category. So does much of production manufacturing. Everyone works, be it with engineering design assistance (design for manufacturability) or new machinery purchases, to squeeze more throughput out of fewer resources.

Figure 2

GSMW workers in the 1930s fabricate architectural metal. In the early days the fabricator made roofing and ventilation systems for the University of Notre Dame.

After analyzing the situation, executives found that GSMW leaned heavily toward this model, but it wasn’t a comfortable fit. This model fits a high-volume, low-product-mix production environment, but GSMW is a fabricator that serves many customers and makes components for a variety of products, each at a different stage of the product life cycle: prototype, production, or aftermarket. Working to squeeze process costs might reduce costs for one product, but would have little to no effect on many others, so the net improvement result was essentially zero.

Axelberg added that their adherence to this model promoted the seemingly endless improvements promised by the “low-hanging fruit”—a change in brake or punch tooling here, another machine arrangement there, a new nesting technique here, and so on. The company had hired continuous improvement consultants, as well as marketing and sales consultants. Everyone had good ideas, and each influenced certain aspects of the operation, but all of this effort didn’t resolve the larger struggles, most of which centered on managing a host of different demands from different customers at the same time.

These improvements didn’t seem to engage talented employees, either. Many had great ideas, some even implemented them on their own, occasionally putting a note in the job packet or setup sheet, but often they just kept it to themselves.

“This wasn’t their fault, really,” Axelberg said. There simply was no formal structure to channel improvement ideas. Instead, most workers seemed to clock in, do their jobs, and go home. “I wanted passionate curiosity in my company, and I didn’t know how to develop it.”

He wanted to change the company culture, but not in an ethereal way. In a sense, he wanted to channel the curiosity and passion employees already had. “These aren’t low-skilled workers. They’re skilled. As we saw it, in most cases they’re really not paid for their repetitive labor, but for their knowledge.”

Lewis agreed. “They are in fact ‘knowledge workers’ as much as anyone who wears a suit and tie to work. Something more fundamental had to be addressed.”

Executives ultimately discovered that, in truth, GSMW’s environment was really suited for the third type of business model, one that focuses on customer relationship management. As Lewis explained, this business model “still pays respect to manufacturing efficiency, but it serves a number of needs through the lifespan of different products.”

Many companies have evolved to use this business model, including banks. Instead of focusing on just checking and savings accounts, banks now offer a range of financial services to many different consumers and institutions. (Some of those products had unexpected, dire consequences, but that’s another story.) Like banks, GSMW works with a range of customers and offers myriad products and services that solve problems at different stages of a product life cycle. The fabricator doesn’t just churn out parts.

In truth, GSMW had for years been straddling two business models. “People here definitely had the customer relationship model mindset, but were constantly being pulled back to the infrastructure-management model, the one traditionally associated with manufacturing,” she explained.

This created that drive toward acquiring better machines and producing more parts per hour. While that’s extremely important, that efficiency mindset didn’t completely align with what customers cared about most. And therein, they realized, should lie the fabricator’s mission.

Figure 3

Last year Taylor Lewis, a business consultant, was brought on to GSMW’s executive team as vice president and chief operating officer.

Discovering a Mission Statement

But what was GSMW’s mission, exactly? Was it to deliver quality products on time? That seemed empty, generic, and not terribly useful. It described the basic qualifications of any topnotch fabricator. It was a ticket for entry onto the competitive field, but it didn’t give anyone a playbook.

Was the mission to provide manufacturing expertise? Again, that seemed too generic. Did customers think about manufacturing expertise every day? Sure, they needed that expertise, but it wasn’t at the forefront of their minds. What did customers truly care about? What allowed them to go home and put food on the table? What kept them sending more work to GSMW, year after year, through the ups and downs of the economy?

After months of analysis and debate, the executives ultimately discovered that, when you get right down to it, it’s not about the customers’ individual products. It’s about the customers’ brands—specifically, their brand’s reputation. That’s what keeps consumers coming back. The brand’s reputation puts food on the table. Uncovering this allowed the executive team ultimately to distill the core of GSMW’s mission statement: To protect customer brands.

“Our big wakeup call was when we realized that [our customers’] goal had to be our goal: to protect their brand, a brand they invest in heavily,” Lewis said, adding that customers needed GSMW for more than “punching out parts.” They needed the fabricator to support the brand and the products that make up those brands, from prototype through production to the aftermarket.

To execute this, Lewis said, the company needed to have detailed labor and process planning, a responsive quality capability, professional engineering and supply chain resources, flexible scheduling, and, in essence, “an ability to respond to a wider variety of our customers’ needs in ways that met their need for cost control, while meeting our need for sustaining profitability.”

The team identified several structural gaps that prevented them from implementing GSMW’s true business model. “The first was that we had no real engineering function,” Lewis said. “We had degreed technologists who served mostly an estimating and some design and support functions, but few degreed or licensed engineers through the years to guide our manufacturing processes and provide higher-level expertise to our manufacturing team and our customers.”

Another gap was employee development. The company had in-house training, but no formal program. There was no structure in place that encouraged idea generation and communication. If a brake operator had an idea for a setup improvement, he just made that improvement, but quite often nothing was documented.

For years the company had operated in typical contract metal fabrication fashion. Orders came in the door, front-office workers prepared those orders and, as Axelberg described it, “lobbed them over the fence to the manufacturing engineers, who would then set up the routings and inspection plans.”

For decades this worked well for GSMW as it served mature, established companies—automotive, lawn and garden, and so on—with years of design and engineering history to draw upon. But recently the company had been doing work for newer, rapidly growing industries, like utility-scale solar, that didn’t have that history. These customers needed design ideas and more engineering expertise.

This represented yet another gap: process-specific engineering leaders, people who could manage specific technology areas like welding and cutting. They also could be a point-person for operators and technicians to discuss problems and offer improvement ideas.

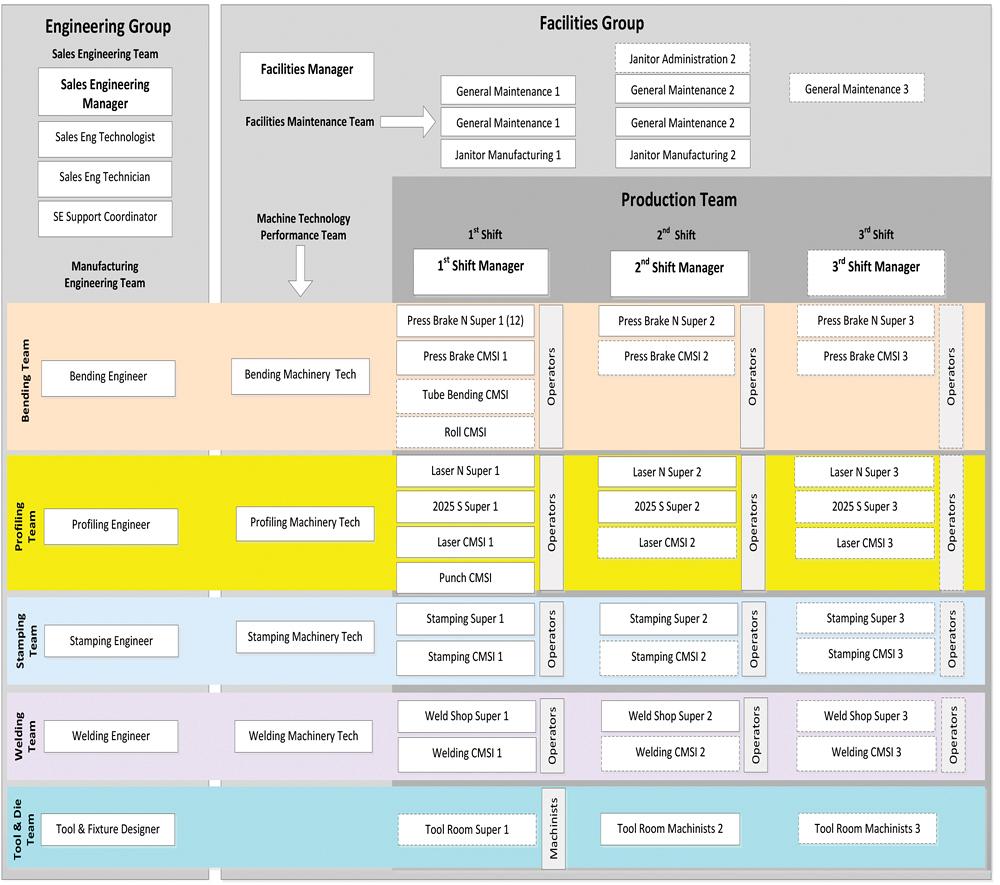

Figure 4

This shows a portion of GSMW’s new structure. Each technology area has its own dedicated engineer, machine skill instructor, and machinery maintenance technician.

The final gap was in supply chain management. Many new customers needed ways not only to distribute and source products, but to protect their own supply chain, and GSMW really didn’t have a team to offer those services.

They knew they had to hire skilled engineers and supply chain managers, and they needed to formalize their training programs, but they also knew they had to do more, because those fixes alone wouldn’t fully address the real problem—the unexpected gaps, the dropped balls, the miscommunication. Whose job is it? Ideally, that question should rarely have to be asked. Lewis summed it up this way: “They saw the big things, but didn’t see the hundreds of interconnected tasks that are the links in the chain of events that lead to a satisfied customer.”

So the company set out to uncover all the links in this chain of events and, ultimately, tailor a new company structure around it.

A New Structure

To develop that structure (see Figure 4), executives didn’t ask who is responsible for a certain task. Instead, they asked “what position” is responsible. The goal: To ensure an unbroken chain of activity that leads to a result the customer wants.

Now, when a job comes in, the entire engineering team works with the customer, suggesting changes and (for some customers) creating new part designs from scratch. They also work with the supply management group, which helps customers overcome sourcing and distribution challenges. This group sources everything from aluminum extrusions to galvanizing and other secondary processing.

The shop floor now is divided into five core technology areas: bending, profiling, stamping, welding, and tool and die (which mainly supports the other technology areas), each led by its own manufacturing engineer. Under the previous structure, these MEs focused on parts. They would catch jobs “lobbed over the fence” from the front office and prepare them for the floor. Now these MEs focus not on part-specific jobs, but instead on the metal fabrication processes themselves.

“They’re not focused just on getting every part ready to run,” Axelberg said. “They’re now working on optimizing the overall manufacturing process.”

Each technology area (except for tool and die) also has a machinery expert, and together they make up a machine technology performance team. They monitor and maintain equipment to ensure optimal equipment availability.

Finally, each machinery area has a supervisor who oversees the operators. Cross-trained operators also can move between certain departments—between profiling and bending, for instance—to handle demand spikes.

According to sources, this structure has several benefits. First, it gives operators a means to voice ways to improve. If they have an idea, be it a new welding fixture or press brake tooling setup, they talk to supervisors and the ME tied to the group. The ME, who is in contact with the sales engineering team and others on the manufacturing engineering team, discusses the improvement and, if it makes sense for everyone, ensures that improvement is documented and communicated for everyone on all shifts. If necessary (say, if the idea is complex or involves multiple departments), they also communicate with the continuous improvement manager, whose job it is to manage improvement projects throughout the company. Ultimately, the improvement becomes a standard process, factored in when sales engineers quote work and at every applicable manufacturing step thereafter.

Figure 5

Under the new structure, the director of cultural development manages several related areas: hiring and onboarding, education and training, continuous improvement, quality assurance, and safety.

Second, the structure fills all presently known links in the chain that lead to customer satisfaction. The sales engineering team covers broader design ideas with the customer. Process-specific MEs ensure those ideas work well for the available machines and tooling on the floor. The machine technology performance team ensures throughput isn’t hindered by unexpected equipment downtime.

Employee Performance

The new structure by itself, of course, doesn’t help much if specific job functions aren’t tied to it. To tackle this, the fabricator took a new approach to human resources and evaluating employee performance.

Axelberg conceded that for decades GSMW really didn’t spend too much time with job descriptions. HR basically treated a job description as a form of legal or regulatory compliance. In fact, executives found that the traditional HR function really is a bifurcated role. One side focuses on benefits (health coverage and the like) and regulatory compliance. On this side, every employee receives the same notices, the same paperwork, the same benefit notices. It’s the side HR is best known for.

The other side, however, focuses on employee development, including performance reviews. Here, ideally, every employee should be treated differently, and performance reviews should be based on an employee’s unique and carefully written job description, edited and polished over time. Executives felt performance reviews should be used as a tool to develop employees, discuss career paths, and identify future cross-training options. It’s the “human” in human resources.

Both sides are needed, but at GSMW, one side—the benefits and regulatory compliance role—tended to dominate the HR function. After all, if a company doesn’t comply with the law and effectively provide employee benefits, it can’t function very well.

For this reason, GSMW split the HR duties into two areas. The benefits and compliance functions were shifted to the finance and accounting department, expanding it to include what the company calls “employee support services.” Benefits and compliance issues relate directly to company finances (health insurance costs money), and the nature of the work fits with the tasks in that department.

Next, the company developed a new position, a director of cultural development, which oversees a hiring manager and education team that includes specialists in curriculum development and training. The position focuses on that “human” side of HR: employee job descriptions, development, training, and career-path consulting.

Specifically, the position manages several functions, all of which are related. A safe employee who produces quality parts probably received more than adequate education and training, thinks continually about improvement, and underwent a carefully planned hiring process. So, thus, the director of cultural development manages all of these departments: hiring and onboarding, education and training, continuous improvement, quality assurance, and safety (see Figure 5).

Moreover, the company took a comprehensive approach to job descriptions to create a solid foundation for its employee development system. “We’ve always had job descriptions,” Axelberg said. “Half of them were pulled off the Internet and massaged a little bit.” He paused, and gave a sigh. “But I’ll be honest: They were virtually worthless.”

Because job descriptions were so generic, employee reviews were generic too, often focusing on an employee’s attitude and general work ethic—nothing specific or particularly helpful, just rote procedure. Now job descriptions are carefully crafted with specific, quantifiable descriptions of daily tasks and work behaviors that can be objectively observed and measured: the ability to read specific blueprints, to use inspection devices, to set up certain tools, to produce the expected level of quality, and so on. Those tasks link directly back to that unbroken chain of events described by the process map that lead to customer satisfaction.

Figure 6

Last year company veteran Kathleen Crimmins took on the new role of director of cultural development.

Accompanying this was a thorough review of salary and wages. To attract and retain the type of employees they wanted, they pored over salary surveys from national, regional, and local organizations to ensure fair and competitive pay. Most important, they linked pay to concrete performance metrics, not just to length of tenure or personality traits.

For years Kathleen Crimmins had worked at the shop as controller, then as director of operations. She knew employees, knew the details of their work, had seen them rise up through the company, and last year took on the new director of cultural development role (see Figure 6).

“In our evaluation of processes, we’ve established roles, and with each one of those roles we have associated job descriptions,” Crimmins said. “The performance development review is based on those requirements spelled out in the job description. So we’re able to measure performance based on their execution of their specific, detailed job description.”

Employees are given a chance to rate themselves, managers do the same, and neither sees what the other has written until the actual performance development review. “To our surprise, we found that people are pretty good at evaluating their own performance objectively,” she said, “and they want to improve.”

She added that this exercise provides the foundation for career consulting, training, and personal development. Where do employees feel they excel? Do others agree? What are the employees’ long-term goals? What do they want to learn? Where do they want to be five, 10, 15 years down the road? Employees now have a forum to voice their opinion of themselves, discuss options, and plan for future opportunities.

Crimmins added that even though she doesn’t deal with benefits and regulatory items directly, she does stay in contact with the financial and support services department, including its head, CFO John Ryal. Close contact is necessary because, of course, things like benefits play a big role in employee satisfaction. “The benefit package has to be meaningful for our people,” she said. “John and I work very closely together.”

What Means What?

Before and during its structural transformation, the executive team mapped out its processes describing every task between getting an order and getting paid for that order (see Figure 7). They built a new organizational structure based on all the tasks necessary to do the job and satisfy a customer. And they wrote (and continue to refine) job descriptions that link to those tasks.

All this required a common language. Like many multigenerational fabrication businesses, GSMW would fascinate a linguist. Over the years, as employees rose through the ranks and became experts in specific areas, they developed their own terminology: Is it a job packet or job traveler? Or is it a job router? What’s the difference, if any, between these terms? And what exactly is a gong? (A gong is a steel parts container, something Axelberg himself thought was named as such because parts made a “gong” sound when dropped in. As it turns out, it comes from “gondola,” jargon borrowed from the rail and shipping business, which refers to gondolas as open containers used to ship bulk commodities like coal.)

Such language is the seed that grows into a confusing forest of tribal knowledge, a severe hindrance to clear communication. So for months executives pored over company documents and interviewed employees. In doing so, they uncovered what exactly meant what. At this writing they are compiling it all into one glossary, so that everyone can learn and speak the same professional language.

“Process mapping was a grueling exercise,” Axelberg said. “It’s really easy to understand why most companies don’t do it.”

A New Physical Structure Too

Axelberg recalled flying back to South Bend. He and a cross-functional group of employees—a sales engineer, a production shift manager, and the bending engineer—were returning from a customer visit. They had been invited for a line walk, during which his team conversed with customer engineers to brainstorm design ideas and take cost out of a product. These visits are much more common now, so much so that the fabricator shares a private plane with several other companies.

Returning home, Axelberg remembered looking at the South Bend headquarters campus from above—four facilities, each with a long history, expanded in segments over time. The oldest was built in 1924. Like so many established manufacturers, the company fights space and line-of-sight problems common in older buildings. Where are parts coming from, and where are they going? The flow isn’t easy to see.

Plans call for a dramatic, unconventional layout. When people walk in the front door, they’ll see a front office surrounded by windows on all sides, providing a panoramic view of much of the shop floor. From most vantage points, people will see how parts flow, in a U shape, from stamping and profiling to bending, welding, and finishing.

“It is designed precisely to support this new structure we have developed,” Axelberg said. “It’s our next step. And it’s really exciting.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI