Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The job shop schedule: Always imperfect, ever adapting

Scheduling software adapts to the tumultuous job shop

- By Tim Heston

- September 9, 2011

- Article

- Shop Management

Say you work at an OEM that outsources to local job shops. A few of them are topnotch, almost always delivering what you need, when you need it. You define about half of them as “average,” delivering on time 80 to 95 percent of the time. Then you have the bottom of the barrel, those that deliver on time less than 80 percent of the time.

According to the 2011 “Financial Ratios & Operational Benchmarking Survey” from the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association, this experience may represent the norm. Twenty-eight percent of respondents said they met delivery deadlines 95 percent of the time or more; 50 percent delivered between 80 and 95 percent on time; and 12 percent reported that they deliver on time less than 80 percent of the time. If they ship 10 orders, chances are at least two are late.

A poor on-time delivery rate is a weighty albatross. OEMs may decide to bring metal fabrication in-house to avoid the scheduling headaches. Metal fabrication job shops themselves may bring processes like powder coating in-house for the very same reasons.

Some expect that in the coming years nearly perfect on-time delivery rates will be what quality is today: a necessity to stay in business. So how can a shop get to near-perfect on-time delivery? Some already have. Consider Mayville Engineering Co. (MEC), a 1,000-employee behemoth of a contract fabricator. Seven years ago the Mayville, Wis., company wasn’t allowed to quote certain jobs because of late deliveries and poor quality. In 2009 John Deere named the fabricator a “Partner Level” supplier, and today Mayville officials say they deliver by the promised due date 99 percent of the time. They are hoping to get that rate even higher. As CEO Bob Kamphuis put it, for on-time delivery, “we want to get to a Six Sigma level.”

How do companies do it? In MEC’s case, the company radically changed how it approached business, and one element included a custom, in-house software system tailored for Mayville’s needs. But whether the strategy is homegrown or purchased, all sources agree that scheduling must adapt to change.

“The only thing constant in a job shop is change,” said Dave Lechleitner, presales principal for Exact North America, Middleton, Mass.

“Job shops can have a daily, complete change in their schedule,” said Bob Geiss, senior consultant at Global Shop Solutions, The Woodlands, Texas. “This affects not only the labor, but also the material requirements.”

Opinions vary widely on how best to handle such unpredictability. Some handle it through Excel. Others use visual scheduling boards, and some use software. And these days scheduling software is very different from that used decades ago. Software vendors tout features such as advanced planning and scheduling (APS), which can integrate with enterprise resource planning (ERP) software designed to account for the variable environment of the job shop. (And yes, software folks love acronyms.)

Whatever the jargon, sources agree that job shop schedules must account for the causes and effects of unexpected schedule changes (from products received late from other suppliers, for instance) and juggle myriad conflicting elements.

Not Just Make-to-Order Anymore

Job shops aren’t purely make-to-order environments. The competitive environment is such that OEMs and top-tier suppliers continue to push more functions down the supply chain, including inventory management. As a result, job shops must work through new wrinkles of business complexity.

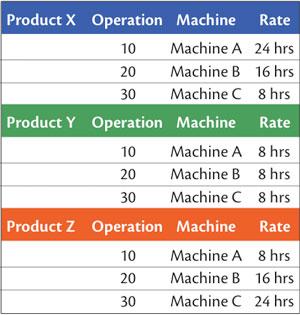

Figure 1: This chart shows three products with routings, along with how long it takes each machine to process these products.

“Although they call themselves job shops, they are balancing and maintaining inventory control for customers now, and so now they’re also getting into forecasting,” said Dusty Alexander, Global Shop Solutions’ president and CEO.

Christine Hansen, product marketing manager for Epicor® Software Corp., Livermore, Calif., described several elements that make job shop scheduling especially complex. “First is having accurate demand, which stems from the initial estimate quoted, detailing how much time it will take to actually produce components. It also stems from the accuracy of the orders and the variability of changes coming from the customer.” Second, every job on the plant floor has pieces of information attached to it coming from various places, and the timeliness of that information is paramount.

Software vendors concede, of course, that no perfect schedule exists, and that the schedule alone won’t fix a shop’s problems. But a schedule that can adapt at least will show accurate information, a snapshot of the current state of shop floor affairs. That state undoubtedly will change again and again. “But we need to acknowledge the changes rather than pretend that they don’t exist,” said Mike Liddell, senior partner at Bradenton, Fla.-based Lean Scheduling International, a provider of APS software.

Opinions vary as to what works where. Take infinite capacity scheduling and finite capacity scheduling. No one argues that fabricating machinery such as laser cutting centers and press brakes have finite capacity. But some say infinite planning has its place, particularly in areas such as assembly and shipping, where various workers and other resources can be shifted around as needed.

Scheduling methodologies abound (forward scheduling, backward scheduling, and so on), and different software vendors may prescribe one or a combination, depending on the situation. But all experts agree that the real world of manufacturing is ever-changing, and the logic behind software must help create a production schedule that can recognize and adapt to those changes. “In the manufacturing world you have thousands of changes coming at you every day,” said Liddell. “Machines break down. New orders come in the door. Jobs take longer than expected, or shorter than expected. Often manufacturers have no way of understanding the implication of one simple change.

“The question you’re trying to answer in scheduling is very simple,” Liddell continued. “What should I do next?”

It Starts With Data

A press brake operator clicks Start on a computer screen, finishes a run, and then clicks Stop. That act of clicking helps create a database of manufacturing times that builds the foundation of scheduling. Any predictive system is only as good as the data put into it, and scheduling is no different.

Some advanced operations have taken the human element out of it, integrating machine controls directly with shop management software. “Some shops do have laser cutting machines that can talk back directly to scheduling programs,” Lechleitner said. “So as the machine runs faster or slower than what was thought, that data will be flowing back in real time, and the schedule can be updated accordingly.”

Order Matters

Sources emphasized how much sequencing matters on the shop floor. Most components require an obvious order of events to occur. A part must first be laser-cut, then bent, then welded and assembled. But when you throw hundreds or thousands of other part numbers into the mix, sequencing becomes a critical factor. Which subcomponent from one order should follow another subcomponent of another order?

Liddell released a book in 2008 called The Little Blue Book on Scheduling.* In it he describes the importance of sequencing by describing three products: X, Y, and Z. Each must undergo three different operations. In Scenario 1, part X can be completed on day 6, Y on day 7, and Z on day 11. Rearranging the sequence of jobs in Scenario 2, though, allows Z to be completed on day 6, Y on day 7, and X on day 8 (see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3).

Liddell writes, “This example shows effectively that the time it takes to deliver all three orders has been reduced by three days—or 27 percent—simply by changing the sequence of events.” He added that the sequencing problem becomes much more complex when the shop must deal with disparate assemblies requiring dozens of components with a multitude of operations.

Nesting different jobs on one piece of sheet metal further complicates matters. “The parts on those nests do not run sequentially,” Exact’s Lechleitner said. “Often we’re nesting five or six different jobs on a sheet, and the jobs might change continually with the product mix. So now you have the nesting software, the laser machine control, and the scheduling system. So we have those variables to contend with as well.”

Scheduling and Setups

In a job shop, setup time reduction, made possible by 5S and perhaps some new machine tools, can change the scheduling balancing act. A new press brake with quick-change, common-shut-height tools capable of staged bending reduces or completely eliminates the setups required on older press brakes. Still, those older brakes may represent capacity the shop could sell, and they could be perfectly productive if they run jobs that require similar tooling setups.

As Geiss from Global Shop Solutions explained, “In order to balance this pool of resources, such as a bank of multiple press brakes, you can distinguish the features that each one of those press brakes is capable of and, if needed, target a certain subset of the larger group to balance the load.”

Another factor is the ability to balance setup reduction and due dates. A scheduling system may group jobs that are due within, say, a three-day range. These jobs may require lengthy setups for each run. On the other hand, if the software looks out over, say, 30 days of orders, it has more jobs to choose from, so it could group similar jobs together to help minimize setup times. Of course, this reverts back to conventional, batch-style manufacturing, with a floor flooded with WIP that waits for weeks until—at long last—all components for a subassembly are complete.

As Geiss explained, “A lot of times the reduction of setup and on-time delivery conflict with one another. Your focus is really on the on-time delivery, and as an adjunct, if you can without disrupting the on-time delivery, you can [group jobs to minimize setup]. There’s a balance.”

These days scheduling software can give options—or “what if” analyses—drawing from real-time and historical data to propose different release times and groupings for various jobs and all of their subcomponents. “It will give multiple versions of the schedule to see what satisfies the best,” Lean Scheduling’s Liddell explained. “Schedules essentially can be simulated, so you can get an accurate schedule that obeys shop floor constraints.”

Those constraints not only include material and machines, but people as well. A machine may have amazing capacity, but if everyone who knows how to run it doesn’t show up for work, there’s a problem. This is why so many lean manufacturing and other improvement consultants have preached the merits of cross-training in the job shop.

This is also where so-called capability-based scheduling comes into play. As Epicor’s Hansen described it, such systems define the capabilities of the machines and the operators who run them. “Regardless of whether an employee is in one department or another, the system knows their capability and can schedule based on that capability.”

Human Element Will Remain

Sources concede that job shop scheduling is just too complex for software to do all the work. “There is always going to be a human element to the decision-making effort,” Lechleitner said. “I think any APS, at its best, will probably get you about 80 percent there.”

Liddell agreed. “The software can do 80 percent of the donkey work, which will let the scheduler do 20 percent of the fine-tuning. We’re not trying to create the perfect schedule. We’ve never seen it work.”

“I have not seen any magical formula,” said Richard Henning, president, Henning Industrial Software, Hudson, Ohio. “You need to monitor the skills people have for specific operations, what machines people are assigned to work on. These are all complex relationships. You still need a human being to help you see the big picture.”

Software doesn’t eliminate the human scheduler, but it does give that person a tool to put some science behind determining delivery dates. Promised delivery dates sometimes are driven more by market pressures, less by actual load levels on the floor. In the desire for work, job shops will take on more work than their available resources can handle.

“Sometimes shops get demands with due dates that are unrealistic,” Henning said, adding that tools are available now that give some insight as to how fast a job can be produced. Knowing current capacities on the floor means there’s less chance a job shop will overpromise and underdeliver.

Key to ImprovementTransparency across multiple levels of a supply chain can help collaboration. Some shops now are using online portals that essentially open their production schedule to their own suppliers—be they for metal, powder coat, plating, heat treating, or anything else—so they can ensure suppliers can meet their demands.

“I see much more communication happening back and forth these days,” Lechleitner said. “A supplier might be able to go to the portal and update a purchase order and due dates, and that information flows back to the scheduling system.”

Be it through online portals or a phone call, communication is more important than ever. If local suppliers can’t deliver on time, a customer’s risk of outsourcing increases significantly.

Sources concede that software alone can’t solve a shop’s on-time delivery problems. Back at MEC, its homegrown software solution was but one of many factors that led to its current success. Scheduling software won’t magically make a dysfunctional shop a world-class operation. But a good scheduling system can increase transparency and record real-time data, giving an accurate snapshot of what’s actually happening at that very moment on the shop floor. Over time these snapshots may help shops pursue any number of improvement efforts. After all, it’s difficult to improve if you don’t have a clear picture of what you’ve got.

*Figures 1, 2, and 3 are from Mike Liddell, The Little Blue Book on Scheduling (Palmetto, Fla.: Joshua1ine Publishing, 2008), p. 51-53, www.littlebluebookonscheduling.com. Reprinted with permission.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI