President

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Why settle for good enough?

Mediocre performance could be the result of leader inertia

- By Woodruff Imberman

- August 20, 2006

- Article

- Shop Management

|

If their financial results are indicative of the manner in which they are run, some steel pipe and tube fabricators need to be managed better.

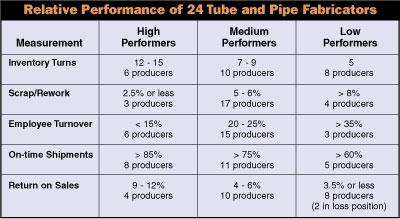

As part of its customary monthly survey of 427 plant managers in the Great Lakes states (Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin), Imberman and DeForest Inc., a management consulting firm, reviewed the operations of 24 steel pipe and tube fabricators that pierce, slot, notch, form, and cut to length round, square, and rectanglar shapes.

Telling Numbers

Only a minority of these 24 showed signs of having well-run, efficient operations, as measured by on-time shipments, amount of inventory and work-in-progress, employee turnover rate, internal rework rates, and, most important, profitability. In fact, a good number of steel pipe and tube fabricators in this sample barely reach the average. Let's look at the data.

Inventory Turns and Working Capital. The rate of inventory turnover is one measure of operational efficiency. Slow inventory turnover indicates excessive inventory and work-in-progress—two items that act like a vacuum cleaner sucking up much-needed working capital. Of the sample 24 pipe and tube fabricators, eight had a sales-to-inventory ratio of 5, and another 10 turned their inventory seven to nine times a year. On the other hand, six ran such lean operations that their inventory turnover was l2 to l5 times a year.

On-time Shipments. On-time shipments—defined as the originally promised shipping date—from manufacturers and component producers suggest well-scheduled production lines and encourage reorders from their customers, the major systems producers who follow them in the supply chain.

Of the 24 companies, eight reported on-time shipments of 85 percent or better; 11 said they shipped on time at least 75 percent of the time; and two said they shipped on schedule less than 50 percent of the time. Another three had such muddled deliveries—partial and rescheduled shipments—that it was impossible to determine their actual performance.

Scrap and Rework Rates. High scrap rates are a waste of time, money, and materials and indicate lackadaisical management and poorly trained workers. Savings generated by reduced defect rates go straight to a tube and pipe fabricator's bottom line.

Of the 24 companies surveyed, most tracked scrap and rework religiously. Three reported less than 2.5 percent internal scrap and rework. Another 17 of the companies reported defect rates of between 5 and 6 percent, and four said their scrap and rework were running higher than 8 percent.

Employee Turnover Rates. For this survey, employee turnover was defined as the total number of employees who left as a percentage of total annual employment. No tube and pipe fabricator reported zero employee turnover. Six reported turnover of less than 15 percent a year, while most of the producers, 15, reported annual turnover rates of 20 to 25 percent. Another three reported employee turnover rates of more than 35 percent annually.

High employee turnover means excessive training and rework costs and poor productivity as new employees learn the ropes. These are severe drains on these tube and pipe fabricators' profits.

Bottom Line: Return on Sales. Profit margin on sales is where the pedal hits the metal, and management skills make a major difference. Of these 24 pipe and tube fabricators, eight reported return on sales of 3.5 percent or less, and another 10 recorded return on sales of 4 to 6 percent. Only four had return on sales of 9 to l2 percent. Two producers were running at a loss and mystified as to why.

|

What accounts for the variation in performance? Interviews with several of these company presidents, vice presidents, and plant managers revealed only two answers: inertia and lack of leadership.

As Peter Drucker wrote in Managing for the Future: The 1990s and Beyond: "Inertia in management is responsible for more loss of market share, more loss of competitive position, and more loss of business growth than any other factor."

In short, good enough seems to be good enough, so why bother about more?

A good number of these executives are satisfied with their company's performance, whether it is a 3 percent return on sales, a sales-inventory ratio of 9, or a 25 percent employee turnover rate.

Why are they content with mediocre performance?

Because improving performance requires more than merely reading the latest pop management tracts about moving cheese or throwing elephants that are hitting the best-seller list. Improving performance requires gathering and then carefully analyzing operating statistics, plus thoughtful planning, talking, cajoling, and then taking action.

Most executives, despite their honest assurances that they strive to improve results, settle for the results reached because they do not want to upset anybody by insisting on better performance. To do better requires too much trouble. So they fall back on the bromide: Good enough is good enough. One perhaps extreme but illuminating example will demonstrate the point.

Inertia

One Midwest manufacturer that makes square and round tubing primarily for the garden equipment and recreation industries was interviewed in-depth for the survey. This company has annual sales of about $20 million, but return on sales was less than 4 percent.

The interview clearly indicated that the president-owner concerned himself primarily with sales, and he had shifted all responsibility for production to a manufacturing manager. The president knew his company regularly received bundles of aluminum tubing from different suppliers weekly, which were cut to length, shaped, and pierced, to be used primarily as handles for the company's garden equipment customers.

Finished components were supposed to be shipped on a weekly basis. But only 70 percent shipped on time. The president didn't know why, and nobody could tell him. Because the company kept no statistics on machine loadings, nobody could say why the bending and piercing equipment was producing at only half its capacity.

And because no reliable records were kept when employees were shifted from department to department to handle production snafus, no good measures of productivity or costs were available. Because quality was poor, original jobs had to be set up and run again. Needless to say, this played havoc with production schedules up and down the line.

A plant tour revealed a remarkable number of bent and dented tubes waiting to be processed. When asked why the company allowed its suppliers to ship defective piping, the quality manager said her suppliers did a good job, and all the defects were due to poor material handling. She implied that it was beyond her span of authority to question why.

When customers complained about a late shipment, extra overtime was routinely ordered to catch up. In addition, on-time shipments to customers normally ran about 70 percent, many of which were partials—and they often were put in the company truck for an all-night speed run to a howling customer.

When queried about his company's high semifinished inventory and work-in-progress—the company turned its inventory 4.5 times a year compared to the industry average of about eight—the president airily dismissed this fact, saying many of his suppliers shipped to him on consignment, so those unfinished parts should not be counted as inventory.

The need for improvement in the plant seemed obvious, so why had nothing been done to make needed changes? The answer: inertia.

The president-owner was happiest concentrating on sales and accepted the mediocre operating results as somebody else's problem. As long as the plant was kept orderly, he had no interest in what went on inside it. He saw his opportunities in the marketplace, and left internal matters to the manufacturing manager.

While this is a somewhat extreme case, interviews with the presidents of other tube fabricating companies revealed that inertia is a common characteristic among the low-margin companies. So long as their companies earned a profit, no matter how meager, these CEOs were satisfied not to rock the boat or try to improve.

In many cases, the CEOs' eyes were focused on the outside world and opportunities in the marketplace. The internal situation bored them. Taking a strong leadership role to improve company performance was not in their psyche.

What Is Leadership?

Leadership is the ability to discern what needs to be done and motivate associates, peers, and subordinates to make those objectives their own priorities. It is a gnawing internal drive to improve, not settle for mediocrity, and dissatisfaction with any performance short of the best.

Leadership is not to be confused with affability, nor, perhaps, popularity.

A top Washington official recently made this comment about leadership:

" ... with leadership, if everybody waited until everyone agreed on everything before one did anything, there wouldn't be such a thing as leadership."

Leaders determine goals and priorities and convey a sense of urgency about achieving them. The presidents of those companies reporting a 9 to 12 percent return on sales exhibited a perpetual drive to improve—a feeling that no matter how well things have gone, they could have gone better if mistakes had not been made, if goals had been fully achieved.

Such drive may not produce popularity, but it does generate respect, credibility, and urgency.

Tools Used

To produce such a high-margin environment, many executives of these high-return companies held annual retreats, in which they employed the talents of outside consultants and specialists to direct and engage the management team in a series of exercises. The purposes of these exercises were:

- To pinpoint what the company does best, and what areas or problems need the most attention and why.

- To review work processes to make them more effective.

- To teach managers to be effective.

- To help managers relate their day-in, day-out activities to their long-term goals so that they can use their time most effectively.

- To determine how these changes are to be achieved, and who will be responsible for their achievement.

- To tie compensation and motivation policies to overall company strategic objectives so employee reward systems at all levels coincide with reaching those objectives.

- To decide what mix of negative and positive incentive systems—some work better than others, depending on employee level—to use as motivators to instill a sense of urgency at all levels to boost productivity, improve quality, and instill the need for the best customer service.

These exercises can be done on a modest budget and can pinpoint problem areas that need to be addressed to improve profitability. They also may suggest which managers and supervisors need coaching and development to reach their full potential.

It's not as easy as reading the latest thriller by some pop management guru on a flight from Chicago to Kansas City or St. Louis, but it should produce better results. And with price competition stiffening, what alternative is there?

Editor's note: The author wrote a follow-up article, "Are you still settling for good enough?"

About the Author

Woodruff Imberman

990 Grove St., Suite 404

Evanston, IL 60201

847-733-0071

About the Publication

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Team Industries names director of advanced technology and manufacturing

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI