Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

A metal fabricator and the art of the (small) deal

South Florida fabricator perfects the bolt-on acquisition

- By Tim Heston

- March 30, 2017

- Article

- Shop Management

When Decimal acquires a competitor, like a local sheet metal fabricator, it often leaves equipment out of the deal if Decimal’s machines—which include an automated laser cutting system—are newer and more productive.

If Alan Garey didn’t coach flag football, Decimal Engineering wouldn’t be what it is today: a $12 million custom fabricator, machine shop, and jaw and chuck manufacturer in Pompano Beach, Fla.

Yes, a jaw and chuck manufacturer. In 2016 Decimal purchased Huron Machine Products, which has been making jaws, chucks, and workholding accessories for machine shops since 1946. Garey, Decimal’s president and CEO, met Huron’s owner through another coach in his flag football league. Their meeting eventually led to a deal, one of seven acquisitions Decimal has made since 1998.

Acquisitions have been a hot topic in recent years, particularly as more shop owners reach retirement age. Fabricators managing by valuation try to diversify their customer mix and reduce revenue concentration. But they also try to grow sales to at least $10 million, so that the transactional costs aren’t overly burdensome relative to the value of a potential deal.

Thing is, most custom metal fabrication—and metalworking in general—occurs in small shops. In survey after survey, many FABRICATOR readers identify themselves as working for a company with fewer than 20 employees. This puts some retiring baby boomers in custom fabrication in a bind. Their immediate family isn’t interested in buying a stake, and because their business is so small, they’re off the financial industry’s radar.

It is here that Decimal has found opportunity. The fabricator hasn’t gone through brokers to get deals done; they’re so small that they really aren’t worth a banker’s time. But taken together, the acquisitions have helped the owners of Decimal grow the company into what it is today.

A Fabricator Family

Garey’s father Arthur (though everyone called him Mike) spent years working for a manufacturer of industrial controls and measurement systems, as a vice president of engineering. “He just got tired of the politics working for a bigger company,” Garey said.

So he went on the hunt for a company to buy, and in 1980 he found Decimal, a job shop launched in 1967. He purchased the shop with family money, including some that was intended to send his three sons—Alan, Mark, and Kevin—to college. In return, he gave them each a 10 percent stake in the business.

In 1994 Arthur was ready to step away, so he handed off the business using a GRAT, or Grantor Retained Annuity Trust, in which his sons purchased company stock over 11 years. Using GRAT helps family businesses avoid estate taxes, and being one of the first GRATs in the nation, it even gave Decimal a little national coverage in Forbes.

Into Machining

Decimal’s first deal came in 1998 with the purchase of a machine shop being divested by Hi-Rel Technologies. In this classic bolt-on acquisition, Decimal hired most of the machine shop’s people (including those with critical machining expertise, which Decimal lacked) and took all of the equipment, which included four CNC machining centers.

Up until then Decimal had strictly been a sheet metal operation. Now it was in the machining business too. And like its later acquisitions, the lead for the deal came not from a broker but from a local connection—this one being one of Decimal’s machinery dealers.

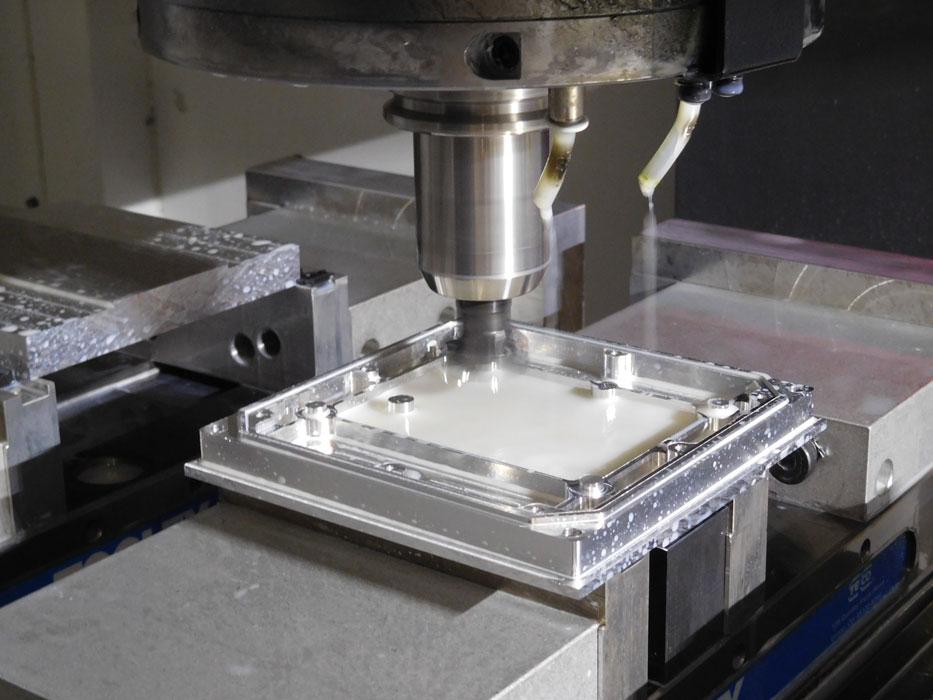

Decimal has been in the machining business since 1998, when the custom fabricator acquired a local machine shop.

The idea of machining in-house had been percolating within Decimal for a while. The company had a few knee mills, but that was about it. At times customers would have work that required both fabrication and machining, and Decimal had been missing out on some opportunities. If the company came across a job that required both, it would either outsource the machining or simply fail to win the business at all.

So when the Hi-Rel opportunity came, the Gareys pounced. The structure of the deal required it; due to its other financial arrangements, Hi-Rel needed to divest the machine shop assets by a certain date.

“We completed that deal in two weeks,” Garey recalled, adding that this included closing the financial aspects of the transaction as well as moving and installing the equipment into Decimal’s facility. “That was a nice, easy transaction. There wasn’t a lot of money upfront, and we took over their leases.”

Cultural Factors

Over the years a few employees from acquired companies have had trouble adapting to Decimal’s culture. It’s a nonsmoking environment, and for safety reasons, Decimal does not allow employees to wear shorts. Some workers from other companies just couldn’t adapt.

But for the most part, the fabricator has never had significant trouble introducing people from acquired companies to the Decimal way of doing things. Garey attributed this to four factors.

First, Decimal has focused on distressed transactions. Garey often works with companies that are having financial difficulty, be it due to a recession or other situations. It’s a little counterintuitive, but shops with financial problems have already endured layoffs, and those who remain are often the company’s best, most productive employees.

Usually Decimal can offer people better working conditions and work culture than they had before. This includes better customer relationships, simply because a shop in financial distress often has trouble meeting customer demand.

Second, the fabricator buys companies that are in the same or similar manufacturing business. It has purchased direct and indirect competitors in the sheet metal fabrication, stamping, and machining arenas, but it has shied away from niches outside metalworking, like plastic injection molding. As people from an acquired company are welcomed to Decimal, they find themselves in familiar territory.

Third, these aren’t massive Time Warner-style deals. Some of Decimal’s acquisitions involved fewer than a half dozen employees. They tend to be small and simple, with no fiefdoms or political intrigue.

Fourth, Garey said he tries to make as many personnel decisions as possible before a deal closes. The deals are small enough so that he can visit the companies being acquired and speak individually with key personnel.

When it acquired a local custom stamper—which ran jobs using both single-station and progressive dies—Decimal found it could retain more business as customer products matured and volumes grew.

In fact, if Garey isn’t permitted to speak with key employees to make sure they’re willing to come over to Decimal, that can be a deal-breaker. These people have technical expertise and important customer relationships, and if they do not plan to move over to Decimal after the acquisition, the deal’s value either changes or falls apart altogether.

“If we have those key people come over, those customer relationships remain intact,” Garey said. “They’re now just wearing a new hat.” Depending on the situation, people may decide to come onboard with Decimal for a year or stay indefinitely. “But even if they stay just a year, it still makes a huge difference.” He added that, thanks largely to this strategy, Decimal has brought over about 90 percent of its acquired companies’ customers.

Getting the Deal Done

In one sense, if Decimal performs good due diligence upfront, it’s usually smooth-going after the deal closes. But Garey conceded that due diligence can be difficult.

The more deals Decimal does, the more calls Garey gets from people looking to sell their business. (A note of disclosure: At present Decimal is stepping back from the acquisition trail to give employees a breather; too many acquisitions can overwhelm the staff and, in doing so, hinder the fabricator’s core mission: servicing existing customers.) When he gets the call, he shops with care, and he isn’t aggressive. Decimal continues to be a successful business, and acquiring yet another firm isn’t critical to the shop’s success, but Garey won’t turn down the right opportunity either.

While Decimal has purchased seven businesses since 1998, it has also walked away from just as many offers. Distressed companies often get extremely low-ball offers, but Garey puts on the table what he feels is fair. Sometimes sellers agree, and sometimes they don’t.

Garey has no problem if sellers walk away; that’s their right. But some situations ring alarm bells. “For a lot of the acquisitions we do, one of the most important things is the seller’s integrity,” Garey said. “Our integrity is equally as important. If we feel the seller’s integrity is compromised, we just walk away.”

Some red flags: A seller significantly overvalues the company assets, or perhaps the stories differ between the seller and his or her employees. A seller may say the shop’s machines are in top shape, and upon inspection Garey finds that they really aren’t.

Garey is also careful because these small deals aren’t done with a lot of lawyer fees—again, just to keep the transaction costs down. The purchase agreements usually are just two or three pages long. “This is another reason why we need to work with a seller whom we trust.”

In fact, Garey considers the time he and his team spend negotiating and working with sellers as part of those transaction costs. Say negotiations are nearly finished; Garey tells his people that a deal is going through, and then the seller backs out at the last minute. That affects employee morale, which also has a cost.

Put simply, if a seller plays games, it’s not worth the buyer’s time. True, some of Decimal’s deals fell apart for other reasons, like machinery was older than expected or customer bases were not found to be complementary. Sometimes basic paperwork—like UCC (Uniform Commercial Code) filings, which prove who owns what—may not be current. But for the vast majority of Decimal’s failed deals, seller integrity problems played a primary role.

Who You Know

Decimal deals locally. That’s partly by design; buying nearby operations gives the fabricator a larger footprint in the local market. But it’s partly due to how the deals come about in the first place. They come from community connections.

For example, Decimal received a lead from one of its local independent sales reps who also happened to represent a custom stamper; the stamper’s owner was looking to sell. Previously Decimal had lost work to stampers as job volumes grew too high for fabrication. But after acquiring a stamper, Decimal no longer lost that work and, most significant, it could gain new work that it couldn’t before.

This deal called for a bit more legwork because it required that Decimal expand its own facility—stamping presses take up space. For many previous acquisitions, Decimal either brought the machines directly onto its shop floor (CNC machining centers don’t take up much space) or, in the case of competing fab shops with older machines, left the equipment out of the acquisition deal. (Those deals were made essentially for the acquired company’s customers and talent.)

Then came the most recent acquisition of Huron, which happened thanks to a flag football connection. It stood apart from Decimal’s previous deals; Huron wasn’t a job shop, but instead had a product line that had been around since 1946.

It’s not unusual for custom manufacturers to want a product line, but it isn’t always easy to integrate into the business. Product lines have different sales and distribution channels, sales structures, and the like. In the past Garey was always careful not to take on a product line that was far outside the company’s sandbox.

But Huron offered workholding equipment for machining, which had been in Decimal’s sandbox ever since its first machine shop acquisition in 1998. Decimal had in fact been a Huron customer itself for many years.

The deal went smoothly, and after operating for six months at another facility (which Decimal rented from Huron’s previous owners), at this writing Huron employees and equipment have moved over to Pompano Beach. As part of the deal, Decimal kept all key sales personnel and machinists, and today those Huron machinists are working alongside longtime Decimal employees.

This wasn’t a bolt-on. Huron still has a dedicated sales and support staff, and the Huron brand remains separate; having such a long history, the brand itself has a lot of value. But now manufacturing of workholding equipment occurs alongside Decimal’s custom work. To workers on the floor, a Huron order is simply another job on the schedule.

The Huron brand is now arguably stronger because it makes use of Decimal’s resources. When Garey purchased the business, it was losing customers because it couldn’t deliver products when needed, mainly because it held no inventory. At this writing, Huron had doubled its sales of certain products, simply because it now carries a certain level of inventory to meet immediate customer demand.

Again, this opportunity would have been missed if Garey didn’t coach flag football. More generally, none of the deals would have happened if Decimal’s managers didn’t participate in community and industry events, including those sponsored by the South Florida Manufacturers Association. They also do a lot of volunteer work in the area.

In this sense, manufacturing is like politics; it happens locally. Without those connections, Decimal wouldn’t be the company it is today.

Images courtesy of Decimal Engineering, 954-975-7992, www.decimal.net.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/30/2024

- Running Time:

- 53:00

Seth Feldman of Iowa-based Wertzbaugher Services joins The Fabricator Podcast to offer his take as a Gen Zer...

- Industry Events

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,